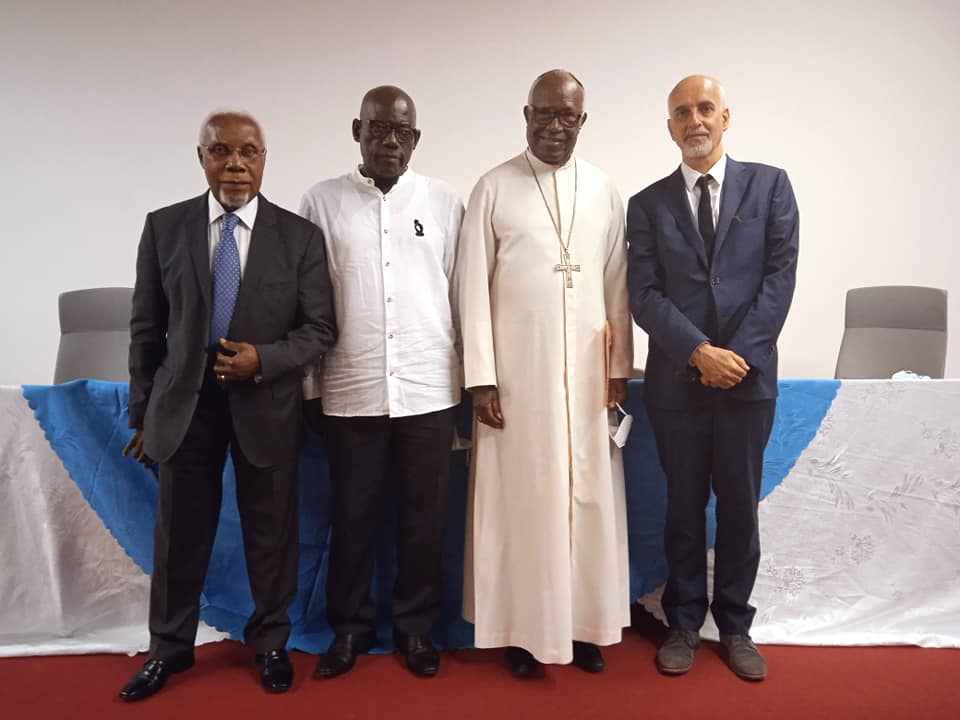

PREFACE: Zacarias Kamwenho (Archbishop Emeritus of Lubango)

Supporting texts for the presentation in London of the work “Os Bantu na visão de Mafrano“

PREFACE: DOM ZACARIAS KAMWENHO

THE WISE MAN AND THE CHEST

“Every teacher of the law who has become a disciple of the kingdom is like the head of a household, who brings out of his storeroom new treasures as well as old.” (cf. Mt 13:52)

I

The family of Maurício Francisco Caetano “Mafrano” has undertaken the noble task of collecting the scattered texts from newspapers and private and public archives of this man who, in my view, was an upright Angolan, a transparent nationalist, a researcher of our culture, and a straightforward writer on cultural anthropology.

This is not a nostalgic exercise, but a necessary contribution to the national cultural fabric that, ultimately, concerns us all, who should collaborate in preserving the values conveyed by the various subcultures of our country.

Personally, I welcomed the initiative, and I thank you for the opportunity to do so publicly, for, as the philosopher Terence said, “whatever is human belongs to me”; in this case, everything written about the Kimbundu genius is part of me, as I am Umbundu.

II

Pope Paul VI — now St. Paul VI — known as “The Pope of Africa,” said in one of his messages to the African continent:

“Many traditions and rites once regarded as strange and primitive are now seen by ethnologists as integral parts of particular social systems that deserve to be studied and respected.”

(Apostolic Letter Africae Terrarum, 1967)

This statement is almost verbatim echoed by the Ad Gentes (AG) Decree of the Second Vatican Council, a decree we eagerly awaited to bring the much-desired breath of fresh air to the process of Evangelisation, as the same Pontiff would say: “An evangelisation that does not touch a people’s culture is a superficial decoration.”

As an elder who worked with “Mafrano,” I express my joy for this first volume and the subsequent ones on “Mafrano’s” profile and his anthropological writings. I also want to say to his family, “Well done!” for this initiative, which will allow us all to experience the joy described in the Gospel of St. Luke when the woman gathers her friends and neighbours to say, “Rejoice with me because I have found the coin I had lost.” (cf. Lk 15:8-9)

III

I will summarise in four points my simple yet profound recognition of Maurício Francisco Caetano:

Maurício and the Second Vatican Council

Pope John XXIII — now St. John XXIII, called “The Good Pope” — announced the convening of the council that would be known as Vatican II (1958–1965).

The Catholic world rejoiced. The objectives of the council were gradually outlined and clarified, as the Constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium (SC) would express in its preamble. While the general public expected the council to shake off the dust that had clung to the institutional church over five centuries (from the Council of Trent to the 20th century), and open windows for fresh air to enter, “the strong wind of the Spirit that sweeps away centuries-old mould,” as John XXIII said, it was indeed the greatest event of the century. Intellectuals were called to collaborate, directly or indirectly, and all the faithful were invited to pray and fast. Maurício Caetano was both a faithful and an intellectual: He prayed and collaborated.

At this time, we were still Portuguese. The Metropolis timidly dictated the paths of preparation. Angola was facing the Colonial War. The political power increased control over the colonies, especially after the independence of Congo-Leopoldville, now the Republic of Congo, on 30 June 1960. Oppress, repress, suppress were the verbs that weighed on intellectuals, believers or not, Catholic or Protestant. However, as St. Paul says, “the word of God is not chained” (2 Tim 2:9).

Some of the Catholic laity of the time rose to the level of their “creed,” particularly in the Capital, where prominent figures like Maurício Caetano, Mendes da Conceição, and António Burity da Silva (senior) became familiar to us, living in the Central Plateau, through the newspaper O Apostolado, or the gatherings organised by the Catholic Church in the Capital or the districts (now provinces).

During this preparation period for the council, its celebration, and its aftermath, the only reliable sources of information came to us through the French-speaking press. Since French was the foreign language taught in Angolan seminaries after Portuguese, this was of great value to Maurício and all of us in following the century’s greatest event: Vatican II. Our proximity to the two Congos helped bridge the gap left by the Metropolis. Congo-Leopoldville already had a strong Catholic University led by Belgian Jesuits, Lovanium.

Maurício, the Conciliator

I will never forget this trait of our “Mafrano” as we evoke his memory.

I arrived in Luanda in 1974 as an auxiliary Bishop. I was 40 years old. A dreamer and timid, confident yet unsure, in large assemblies I sought familiar faces, which I didn’t always find. One of those faces would have been “Mafrano’s,” because in the various provincial meetings, his family, like others such as the Espírito Santo Vieira family or that of Bishop Emílio de Carvalho, welcomed me into their homes and greatly helped me navigate those who questioned the appointment of a bishop from the Central Plateau (Umbundu) to the capital city (Kimbundu).

Maurício Caetano had a special opportunity to demonstrate his conciliatory charisma. It was during my first pastoral visit to Golungo Alto in 1975, before the proclamation of Independence. We met there, providentially, I would say: he in the service of the State in the finance field, I in pastoral ministry. During the customary formal greetings, I felt relieved when I shook his hand, as I did with the others.

After dinner, he came to the parish residence. He brought a timely word and confided in me:

“Tomorrow, at the meeting with the parish’s key figures, don’t be alarmed if someone asks for a ‘point of order’ during the Q&A session. It’s a group of ‘revolutionary youth’ who will ask permission for a parish consultation point, which is a polite way of saying, a public trial of the parish priest. When the young man finishes speaking, I too will request a ‘point of order’ so that you won’t have to respond.”

No sooner said than done. When he spoke, with the authority recognised by the older catechists and the youth who knew him well, “Mafrano” drew upon tradition, the history of the MPLA, without forgetting biblical arguments. He finished with two or three questions that silenced the so-called “revolutionary” group. Relief for the elders who had no courage to contradict the youth and risk being called reactionary, obscurantist, etc.

After the silence that followed this layman’s committed exposition, I had little more to say than to thank everyone for coming to meet the new Pastor and to give them the final blessing.

Maurício, the Christian Scribe

Inspired by Vatican II, “Mafrano” read and implemented the Gaudium et Spes (GS) Constitution, particularly where it says: “More and more men and women of every group and nation are becoming aware that they are the artisans and authors of their own community’s culture.” (Gaudium et Spes, 1965, n. 55).

“Mafrano” answered, “present!” Although he did not leave us a book, what he left scattered in newspapers and archives forms a collection now published in four volumes, of which we are currently presenting the first.

A distinguished student of the Luanda Seminary, where he studied Philosophy and Theology, colleagues and teachers nicknamed him the “library rat.” He once confided in me that for him, the long holidays were a continuation of his formation. “The library continued in listening to the ‘elders’, and they too felt gratified and entrusted me without hesitation with their secrets,” he said.

Maurício, the Artisan of our Culture

In weeks of study or in specific conferences on cultural anthropology, Maurício Caetano had to be present. Father Raul Assua, a Basque priest and author of the book A Cultura Bantu, admired “Mafrano” and enjoyed discussing topics of mutual interest with him.

It was interesting to hear them, especially when the discussion heated up: one would refer to an African author, the other would confirm the phenomenon in question with firsthand experience. In the end, we all benefited.

I witnessed this in 1977. I invited Maurício to lead the study topic at our Diocesan Pastoral Assembly. The theme was: Traditional Marriage and Its Implications in Canonical Marriage.

We received a masterful and interesting presentation that lasted an entire day, and the following morning, we drew conclusions and recommendations to apply throughout the pastoral year.

“Mafrano” proved himself to be a master, a scribe who, as St. Matthew says, took old and new treasures from his chest, illuminating them with the light of the Gospel. Starting from the “Alambamento” (traditional dowry), he guided us through to the “Separation of Spouses” by divorce or death.

He provoked dialogue: accepted criticism like a wise man, clarified the doubts and prejudices of listeners like a teacher and educator. We saw him take notes of opinions different from his own, and the more he admitted his limitations, the more he won everyone’s admiration. We were in the presence of an artisan of our culture.

Father César Viana (from Kibala), a young and dynamic member of the Pastoral Secretariat, delivered a heartfelt and deserved tribute to the speaker in his closing remarks.

“Mafrano,” true to himself, replied with a proverb common to many African subcultures that, when translated, roughly says:

“We, the elders, the scholars, prepare for you, the young, rustic sandals for you to walk toward the land where you will find everything, including shoes; wear these shoes, but never forget the sandals.”

CONCLUSION

I conclude, happily, by bearing witness to someone whose memory I personally wish to be eternal.

— Eternal like the word munthu, mu- (person) + -nthu (being), which once appeared in history and left (and continues to leave) traces, like a river that does not change its name but whose waters flow to the sea (kalunga), giving life from generation to generation;

— Eternal, for these “sandals” that the “Mafrano” family has now gathered. They were forgotten in the corners of our house (Angola), but they still speak of the anthropologist and his time;

— Eternal, for the contribution made to implementing the great lines of Vatican II and other post-conciliar documents like Evangeli Nuntiandi (1975), through articles and conferences.

Well, my friends: in the global city, we know there are winners, losers, and survivors. Like Maurício Caetano, however, we will know how to say: Present! National reconstruction depends on the reconstruction of each one’s identity (the awakening to munthu), in our case within Lusophony.

In the history of the Catholic Church in Angola, there were men who believed in that munthu. On a religious level, I would recall the name of Ernesto Lecomte, a French Spiritan priest, who, in becoming “black with the blacks,” as advised by the founder of his congregation, managed to translate into some of our languages the catechism of St. Pius X, which guided us to the current Catechism of the Catholic Church.

For all this, and keeping in mind the social and anthropological studies emerging throughout Angola, I place on Maurício Caetano’s lips the words with which Pope Francis ends his Apostolic Exhortation, Christus Vivit, addressed to young people and the entire people of God:

“The Church needs your enthusiasm, your intuitions, your faith. We need you. And when you arrive where we have not yet reached, have the patience to wait for us.”

(Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation Christus Vivit, 2019, n. 299)

Lubango, 4 March 2020